>

>

How To Play Great Fingerpicking Guitar--Even If You're All Thumbs!

Chapter 9

LIGHTNING HOPKINS STYLE 12 BAR BLUES

The “twelve bar blues” is the most common blues form, and most improvisers start with it.

It is so universal that it bears a bit of explaining.

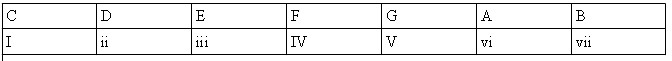

The twelve "bars" are MEASURES. They almost always follow this pattern:

What's all this? Why Roman Numerals?

They represent the CHORD LEVELS in a key. There are seven notes in a major scale. Any of these could be a "root" note to build a chord on. Thus there are seven chords naturally in a key. Each root can have a chord built on it.

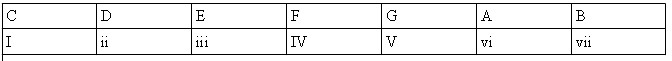

For example: in the key of C, there are seven notes in the C Major scale:

>

>

Each one of these notes could be the root for a chord:

Cmaj Dmin Emin FMaj GMaj Amin Bdim

In a "12 Bar Blues" you'd usually use chords built on the I, IV, and V Roots.

Most of the time they'd be "Dominant Seventh" chords--often called "Seventh" Chords. However, this "Seventh" is not what root they're based on, but the last of the four separate notes that make them up Root, third, fifth and Seventh.

Still there? Yes this is confusing. You don't have to absorb all of this to play the blues...

Most 12 bar blues use I7, IV7, and V7 chords. "Seventh" chords have a tension to them: they want to "resolve" or go to another chord. This means they won't "stand still." Usually a I7 wants to go to the IV7, and the V7 wants to go back to the I (or I7).

Because they're all "7ths" they lead us into expecting change, and the music keeps jumpin'.

The number of a chord in a key depends on what key it is. For instance, the first note of "the key of C" is C. This comes from the scale associated with that key.

Thus in the key of C, the I7 chord is C7, the IV7 chord is F7, and V7 is G7.

Twelve bars of such a blues in the key of C would be:

Let's take another key, such as the Key of E (a popular blues key): I7 becomes E7, IV7 is A7, and V7 is B7, based on the notes of the E scale.

The 12 Bar blues pattern for this key is the third row above -- it starts with E7.

Had enough? Well, if you use the

Just start with the chord matching the first note of the scale of that key (the I chord), and count slowly.

Of course, Lightnin' Sam Hopkins of Texas didn't bother with any of this. He just played 'em. And played 'em. But since most of us won't be playing 12 bar blues twelve hours a day, every day, it helps to use some music theory, so we can sound like him.

Such as about TRIPLETS, which Lightnin' played unconsciously (but the rest of us aren't so lucky).

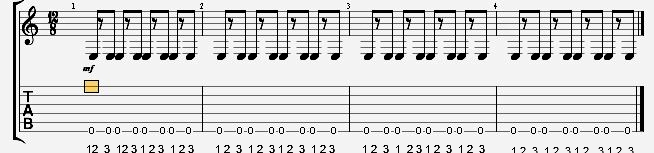

Most Hopkins/Lipscomb/James Taylor (ha, fooled ya) styled blues is accompanied by a driving bass in THREE. That is, three counts per beat. Yup, those old bluesmen were plenty crafty.

Imagine the four quarter note bass notes per measure that we've finally gotten used to suddenly mutating into three equal parts each! It can't be blamed on radiation, but you can collect these notes into FOUR equal groups.

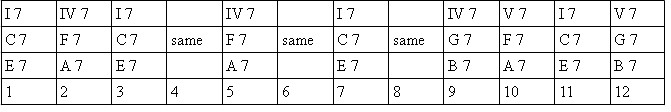

Yes, Four groups of Three:

Count it this way:

bass-bass-bass bass-bass-bass bass-bass-bass bass-bass-bass

Give the

FIRST of each of these groups of three an emphasis:

Here's what we end up with:

BASS-bass-bass BASS-bass-bass BASS-bass-bass BASS-bass-bass

But Wait! Real blues players DROP the MIDDLE BASS!

That is, they COUNT it but DON'T SOUND it.

Arrgghh!!

So we end up with:

BASS(rest)bass BASS(rest)bass BASS(rest)bass BASS(rest)bass

Better yet, LET THE FIRST BASS NOTE RING THROUGH THE REST on the second count. That's what the bluesmen do.

Now it'll comes out:

Counting it out, as all good musicians should, you would count:

1 (silent 2) 3 1 (silent 2) 3; and so forth.

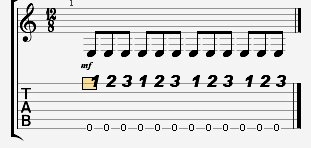

This is now a typical measure of 12 bar blues:

Whaaa? Relax... it's easier to play than to try to explain.

Try counting out the

LOONG short example above,

(1--2-------3 ).

or listen to Me playing it in the 1990s

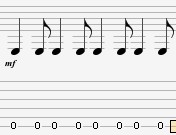

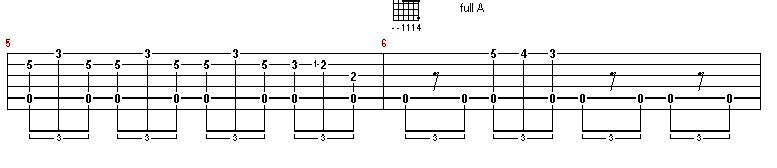

Well it's about time! For those of you who just skipped the above....I hope you're extremely lucky! Let's start with the FIRST TWO MEASURES:

MEASURE 1 then 2

MEASURE 1:

If a beat only has a bassline, DON'T RUSH IT! Play the basses evenly, or the blues won't groove.

Remember to count each measure:

LOOONG short, LOOONG short, LOOOONG short, LOOOONG short 1 2 3, 1 2 3, 1 2 3, 1 2 3

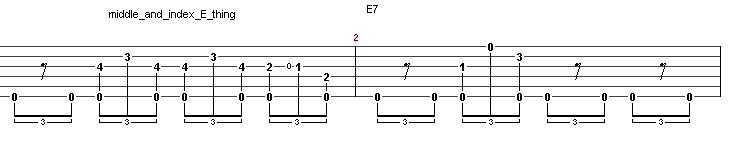

MEASURE 3 is similar to measure 1, with variations:

These are all based on the E7 "sound" that come from sliding the D7 around but they're all different "licks" or musical phrases.

Back to the normal E for Measure 4.

Measures 5 6 introduce a new A7 blues form:

It's just two fingers on the 3rd string 5th fret (Left Ring) and 1st string 3rd fret (index).

Measure 5:

Measure 6:

Measure 7: based on measures 1 and 3.

MEASURE 8:

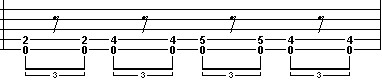

This is a terrific bass technique I call the "blues bass." It's the most widely used rhythm sound in blues, early R & B, and guitar based rock, and I'm going to explain it to you atNo Extra Charge (incredible, isn't it--but maybe after the previous 7 measures of this blues I've lost you all anyway).

Using the above, here's Measure 8:

This is the lick that the Rolling Stones made millions on. I'm letting you have it for practically nothing! The least you can do is practice it a little.

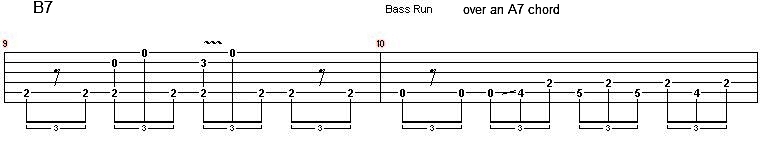

Measure 9: The B7 is played WITHOUT the Pinky on the first string. Use it for the first note in Beat #3 (and pull on it a little); But lift it for the next note.

Measure 10: Now here's a nifty bass run! This is a classic "Lightnin' Sam A7 lick"--a run to be played on the bass strings, in the space where a rhythm guitarist would play an A7 chord.

Note that you are now playing all three notes of the triplet here in beats number 2, 3, and 4. Emphasize the FIRST of each triplet. This is true of EVERY measure of this blues.

If you've learned this concept, you should have four stressed bass notes in every measure.

Hmmm. That is, if you're not over-stressed yourself by now! Take this piece one measure at a time. It's a great deal more difficult than our previous challenges, but it's the KEY to playing acoustic blues with one guitar. You can play it over and over, once we cover the last two measures--the turnaround.

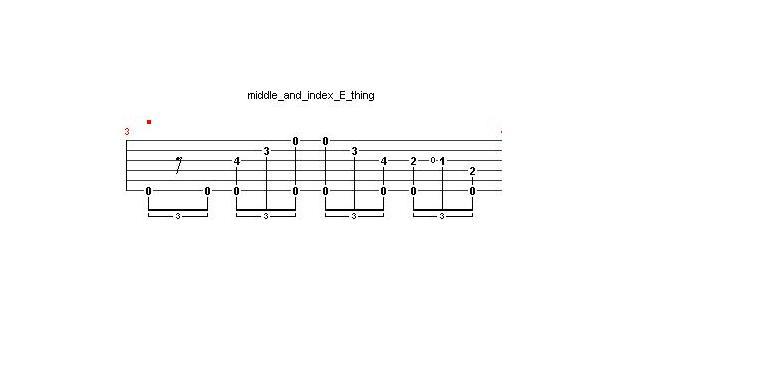

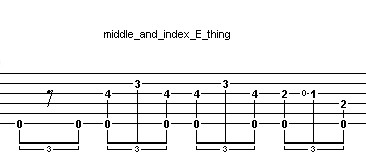

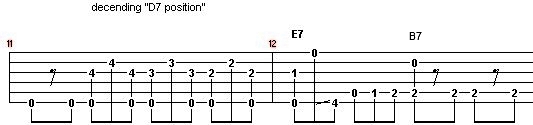

THE TURNAROUND

The final two measures of a chorus of blues is supposed to get you to the Next chorus, to "turn you around" to start over and play another 12 bars. This piece uses the most common blues turnaround:

Measure 11:

Measure 12:

This "turnaround" goes from the I chord in this key (E) to the V7 chord (B7). It leaves you hanging--wanting to hear another "I" chord. That craving is best satisfied by playing the blues again from the beginning.

This is the style of not only 1) old Southern blues, but 2) recent tunes such as James Taylor's Steamroller. It's the basis of other (not necessarily 12 bar) blues such as Dave Van Ronk's (and Snooks Eaglin's) Come Back Baby.

If it seems really hard--well, it is! But it's just about THE major blues style, and well worth your effort. You CAN get it if you go over it in little modules, slowly. I sure had to!

|

Back to the Table Of Contents |

Trouble reading tablature?: Tablature Help Here |

More info/contact Andy:

http://www.andypolon.com_